(Note: This past week marked the birthdays of Ray Bradbury and H.P. Lovecraft. I’m willing to go out on a limb and say that they are perhaps two of the most influential American writers of the 20th Century. Perhaps that’s overstating it but, at the very least, readers and writers owe a great deal to them. Oddly enough, they’re also two of our most dismissed authors, easily relegated to the genre ghettos of our libraries and bookstores. This irritates me.)

(And so…)

In his introduction to The Dream Cycle of H.P. Lovecraft, Neil Gaiman writes this lovely description:

“If Literature is the world, then Fantasy and Horror are twin cities, divided by a river of black water. . . . H.P. Lovecraft is the kind of long street that runs from the outskirts of the first city to the end of the other. It began as a minor thoroughfare, and is now a six-lane highway, built up on every side.â€

It’s an excellent essay and worth reading.

I’ve been thinking a lot about genre lately, and how ineffective a tool it is.

Take, for instance, the Fantasy genre. As a label, Fantasy summons very distinct (and sometimes conflicting) interpretations.

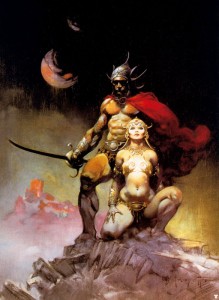

If you’re of a certain age, it’s going to immediately evoke the full painted images from someone like Vallejo or Frazetta — Musclebound barbarian types rescuing scantily clad cheesecake damsels from sabertooth tigers. For others, invoking the Fantasy label immediately places a work on the shelf next to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, or Terry Brooks. Sometimes talking animals in waistcoats or chain mail are involved.

If you’re of a certain age, it’s going to immediately evoke the full painted images from someone like Vallejo or Frazetta — Musclebound barbarian types rescuing scantily clad cheesecake damsels from sabertooth tigers. For others, invoking the Fantasy label immediately places a work on the shelf next to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, or Terry Brooks. Sometimes talking animals in waistcoats or chain mail are involved.

And then there’s the more common contemporary reaction: “You mean like Harry Potter?â€

Put it another way, the genre is the cliche.

Whatever the label Fantasy evokes, it’s likely that most people you know — and, perhaps, even you — look on these authors and their works as quaint relics of adolescence, childish things to be put away when a reader’s literary palette has matured. At best, there’s a nostalgic fondness for them. At worst, they’re not fit to keep company with proper Literature.

You know this is true. Go into any bookstore. There’s Fiction over there, Non-Fiction over there . . . and then maybe a couple of shelves crammed with Horror, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Mystery, Romance, etc.

On the shelves here in my house, the books are organized in a fairly simple system. Prose, poetry, and theatre are arranged together, alphabetically by author. I also keep the literary biographies in that same group, next to whatever author they relate to. Which makes perfect sense to me. As a reader, I don’t necessarily limit myself to a specific section of the bookstore or library. And as a writer, I find genres to be a fairly worthless system for most of the parties involved.

During the past few years, I’ve been in a couple of stores that didn’t segregate fiction. And it was excellent to browse books without having to seek them out in their little retail neighborhood — although “ghettos†might be a more appropriate word in this instance.

Having spent most of my professional life in marketing and/or advertising, it’s difficult for me not to assume that the concept of genre originated in the boardroom rather than the mind of the author. It’s fairly obvious to me that genre is a business construct, not a creative one. I’m sure that assumption is inaccurate and perhaps even unfair. I know that the application of genre isn’t a corporate conspiracy and it likely represents a gentle evolution of how books have been marketed.

And really, it doesn’t matter who made the world, who built the cities. They’re there now and we get around them as best we can.

The problem is that the majority of authors don’t know when to stay in their proper place. And neither do their stories.

Take Lovecraft, for instance. Admittedly, much of his work can be classified as Horror . . . except for many of them which paddle through the shallower waters of Suspense, except for the numerous stories that also dip their oar in Science Fiction as well.

And then there’s Ray Bradbury. If Lovecraft is a slow boat ride through the darker backwaters of fiction, then Ray is driving a speedboat full bore across every stream and channel, blowing everyone’s hair back. He’s obviously a Science Fiction writer, of course . . . so long as you don’t count the majority of his writing, most of which is obviously not Science Fiction.

There are authors who are proud to be a _________ writer. But for each writer who wears their genre like a badge, there are plenty of others who seem ashamed for writing in whatever backwater to which they’ve been relegated.

I don’t have a beef with any of them, really. May their gods bless them.

I don’t pretend to speak for anyone else.

For my part, as a writer, I don’t think about genre. I don’t think about my own work in those terms.

Publishers and agents do, of course. It’s necessary, one of the underlying structures of that industry. Which means that retailers, for the most part, follow suit.

Which means that readers, for the most part, do the same. I’m sure that if a store the size of Barnes & Noble (for example) had one big section called Fiction, it would be nothing short of a nightmare for everyone working there. Imagine the countless questions from customers conditioned over decades to look for what they want according to genre.

Although it would be somewhat easier to stock the shelves.

For me, all of this whinging comes down to the incredible difficulty of fitting my own work into a genre. Whatever I choose, the danger of misinterpretation is high.

For example, “Assam & Darjeeling†is a Fantasy. Except for the parts which are Horror. Except for the parts which are Suspense. Except for the parts which are Fairy Tale.

Which is just too bad for me, with all my agent queries.

The latest genre I’ve heard in use is Speculative Fiction — a label that, to me, is astonishingly similar to the use of Graphic Novel in the comics world. It is a term born of shame, a desperate attempt at self-legitimacy, a false passport in order to escape our second-class neighborhoods.

And, like anything else, it concedes the point it attempts to refute.

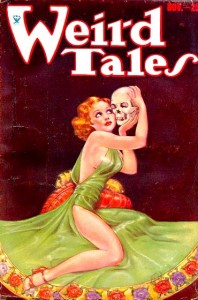

A few days ago was H.P. Lovecraft’s birthday. Reading Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac for that day set of a chain reaction of sparks in my mind: “[Lovecraft] wrote science fiction, fantasy, and horror, a genre that during his life was called simply weird fiction.â€

A few days ago was H.P. Lovecraft’s birthday. Reading Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac for that day set of a chain reaction of sparks in my mind: “[Lovecraft] wrote science fiction, fantasy, and horror, a genre that during his life was called simply weird fiction.â€

This same chain reaction led me to the dictionary and an astonishing definition of the term weird: “Suggesting something supernatural; uncanny. . . . very strange; bizarre. . . . connected with fate.â€

The root noun wyrd is from the Old English and it meant “a person’s destiny.â€

Ladies and gentlemen, we have a winner.

Like most of what I write, “Assam & Darjeeling†is a Fantasy. Except for the parts which are Horror. Except for the parts which are Suspense. Except for the parts which are Fairy Tale.

In short, it is Weird.