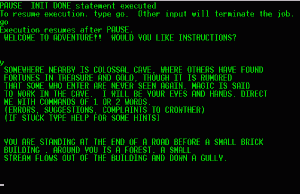

“Welcome to Adventure!! Would you like instructions?”

The table was octagonal. Above it hung a globe of frosted glass set inside an inverted basket — a relic of the earthier home decor from previous decades, when remnants of the handmade counter-culture were co-opted and made legitimate by the middle class.

The table was octagonal. Above it hung a globe of frosted glass set inside an inverted basket — a relic of the earthier home decor from previous decades, when remnants of the handmade counter-culture were co-opted and made legitimate by the middle class.

Somewhere in the world, godless Commie hippies worked on their communes, gathering their crops of marijuana and poppies in large baskets appropriated, like their drugs, from Asia.

Contrariwise, my respectably middle class, conservative Christian mother flipped a basket over, made it into a lamp, and hung it from a chain in our family room. This was creativity and interior design. This was evolution. Hey… it was the late 70’s.

We sat in the irregular pool of light it cast on the table below, I on one side and my friend Benny on the other.

The table, perhaps three feet across from side to side, was bare between us. My memory stains it the color of old honey, inlaid with darker panels in which knots float in the polished surface. I never cared much for that style. It unnerved me.

It was everywhere in those days — furniture, paneled walls, car dashboards — the dark swirls rising like the gaping mouths and faces of those calling out from the Underworld.

Yes. I was that kind of child.

I wonder where that table is now?

“You’re at the end of a road. There’s a building in the distance.”

I can hear his voice . . . even still, even now.

I see Benny’s face there across from me, the flat gaze staring back. Almost a challenge, almost a dare.

This was no mere game, I understood. This was a serious undertaking.

Our friendship was a fluke, really. An alphabetical accident, forced together on the first day of school by a seating chart and the coincidental conjunction of our last names. He sat to my right. I do not recall who was on my left.

By then, I’d changed schools more than a few times. I knew what it meant to be The New Kid… To be outside of every joke, disconnected from the local customs and history… To puzzle over the unfamiliar rituals, to try and suss out the relationships and social order… To fail at all of these, to be awkward and unknown.

By then, I’d changed schools more than a few times. I knew what it meant to be The New Kid… To be outside of every joke, disconnected from the local customs and history… To puzzle over the unfamiliar rituals, to try and suss out the relationships and social order… To fail at all of these, to be awkward and unknown.

Our teacher’s name was Anita Niblett. She was, she told us in her strangely accented seagull voice, from Georgia. Neither of these things are significant in and of themselves. They merely added to the strangeness of the day.

Seventh grade. Never the easiest time for anyone. But it should have been easier. This was a new school, established that same year to serve as a feeder for a local high school. All the teachers and students were starting fresh on Day One. We were all The New Kid, in our own way.

But not really. It was clear that first morning that most of the other kids had a history, knew each other from previous schools or from their churches or little league. That made it worse somehow. I’d been counting on the promise that everyone would be new. It had been a selling point, my parents smoothing over the rough patch between my old school and yet another change.

And now, sitting there in the front row of Miss Niblett’s class, I discovered that I was the outsider yet again.

“Across the chasm, you can see a window high up on the opposite wall. There is a figure in the window, trying to get your attention.”

I wasn’t alone. This kid on my right, he was obviously as disconnected as I was. Neither of us knew anyone. And so we were forced by proximity and alphabet to make small talk with each other. It was either that or sit silently in our own little bubble of shame.

I remember the awkward introduction, the odd rhyming intonation of his first and last name. I might have said something about it, made a joke. I don’t remember. I’m sure we must have spent some time sounding the other, me and Benny . . . like lost cavers calling out and listening for echoes, hoping for familiar landmarks.

“You are in a maze of twisty little passages, all different.”

That’s what you do as kids, meeting someone new: You conduct a quick survey, looking for continuity in musical taste or favorite television shows or sports teams. My experience in most of these did nothing but distance me further from other kids. They didn’t read comics, I didn’t play sports. I wasn’t yet interested in pop music and they’d long ago given up their action figures. I’d been getting used to less and less common ground with anyone.

That’s what you do as kids, meeting someone new: You conduct a quick survey, looking for continuity in musical taste or favorite television shows or sports teams. My experience in most of these did nothing but distance me further from other kids. They didn’t read comics, I didn’t play sports. I wasn’t yet interested in pop music and they’d long ago given up their action figures. I’d been getting used to less and less common ground with anyone.

Memories are vague, nearly thirty years later. But I remember that, somehow, at some point, Tolkien was there. Perhaps one of us had a book — the dogeared copy of The Hobbit that I’d stolen from my older brother and read obsessively. Or maybe Benny was the one with the book and I noticed it there on his desk.

Maybe we just started talking and, luckily, the gods were there to throw down a cable in a form that would be familiar and comforting to us both. However it happened, we managed to grasp the line, desperate not to be lost here. Not alone.

“It is now pitch dark. If you proceed you will likely fall into a pit.”

It’s one thing to make a new friend, to hang out at recess and during lunch. But the real test comes with the first sleepover — the after school ride home, opening the door to a stranger and letting them into your private world… Wondering what they are thinking of the house, of your family… Suddenly aware of the lingering stuffed animals on your bed, the Star Wars toys still in circulation on your bedroom floor, the comics and books on the shelves…

Can you stand each other’s company outside of the classroom? Is there more to your friendship than just the playground alliance you’ve formed?

Hell, can you manage to get through a night without getting bored or sick of each other?

Harder than it sounds, especially back then. This was before the Internet, of course. Before video games and home computers. This was before cable television and the VCR. Looking back on it, I wonder how the hell we ever managed to fill the time.

At some point after dinner, we ran out of things to do. Benny suggested we play a game. I have a vague memory of him describing something he played, something on one of the computers at his dad’s office — I had only the faintest idea of what a computer even was, really. But Benny seemed to think that we could play this game. The lack of technology wouldn’t be a problem.

He knew the game, practically had it memorized. He would be the computer. I would be the player.

We sat down at the table in my family room.

The name of the game was Adventure.

“You’re at the end of a road. There’s a building in the distance.”

And with a simple sentence or two, we were off and running. I would listen to Benny’s descriptions and then suggest a direction or an action. He would then provide me with the next description or obstacle or puzzle.

Almost immediately, I was hooked. Time and distance might be exaggerating the memory in my mind, but it seems to me that we stayed up until well past midnight. I don’t know how far along I got in my inaugural exploration of the cave. I recall the hollow voice saying “Plugh” so I know I at least made it to Y2 on that first outing.

I remember learning the vocabulary of the game, the limits of the two-word command. The peculiarities of the descriptions and how the word “look” would only tell me so much about my surroundings. I remember testing the boundaries of the world itself, finding my bearings.

And I remember spending a long, long time trying to get the attention of the person in the window on the opposite side of the chasm.

Benny was incredibly patient with these experiments, given that he’d been playing the game for a long, long time and already know most of its secrets. I got lost in no time in a maze of twisty little passages. I was probably doomed. I wasn’t smart enough to systematically find my way out.

But I did. He probably let me off easy, let me find my way out even if I didn’t deserve it.

It occurs to me now that it must have been a bit boring for him.

“I will be your eyes and hands. Direct me with commands of 1 or 2 words.”

For my part, I was having a grand old time. I can’t say why that was, exactly. I suppose it was a bit like being a character in a book — playing the role of reader and protagonist alike. Some of it had to do with the intrinsic value of this sort of game — just enough description to let your mind visualize the whole thing without defining someone else’s vision instead of your own.

Everything he described, I could see it perfectly in my mind. I can see it even now. It is unchanged, nearly thirty years later.

I feel nostalgia for that place. I dreamed of it often.

I dream of it still.

“There is a threatening little dwarf in the room with you!”

A surprise, to find I wasn’t alone in this place. And there was danger here, more than just a false step or a wrong choice.

A surprise, to find I wasn’t alone in this place. And there was danger here, more than just a false step or a wrong choice.

Benny said the words and my mind readily called the dwarf into being. I’d read Tolkien. I’d seen movies. I knew what dwarves looked like, what they should look like.

But my imagination had other ideas, filling in that particular blank with, inexplicably, an illustration from an old Legion of Superheroes comic.

Odd how the mind works, the way it bridges gaps with whatever raw material it has at hand.

“It is now pitch dark. If you proceed you will likely fall into a pit.”

It was inevitable that we’d shift from playing the game to making up our own.

It was inevitable that we’d shift from playing the game to making up our own.

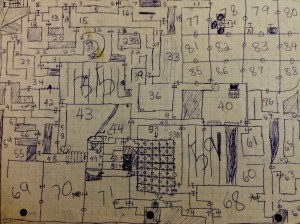

After that night, my life revolved around adventures. I didn’t go anywhere without a binder packed full of scribbled notes, sheets of graph paper tracing out the careful walls and pitfalls of our my dungeons and mazes. These I populated with traps and puzzles, characters and monsters culled from my books on mythology and from faerie tales… from Lewis and Tolkien… from my own imagination.

We sat at recess and during the lunch break, Benny and me, our heads bowed over our notebooks and graph paper. We employed any excuse to duck the excruciatingly dull PE session in the afternoons. I found new reasons to ignore my homework in the evenings. I scribbled ideas in the margins of sunday school handouts and the church bulletin.

I was, without realizing it, taking my first steps as a writer.

“With what? Your bare hands?”

We killed a dragon once, he and I together. We were playing the game properly, on a computer at his father’s office. His parents had dropped us off in the morning on Saturday and we’d spent the whole day — most of the evening as well, if I’m remembering correctly — exploring the cave together.

There was a dragon on a Persian rug and, like most of its kind, seemingly invulnerable to any attack or trick.

In a flash of insight, we defeated it with a single word.

Exuberance doesn’t begin to describe our triumph. It was a proud moment, to say the least. I still feel a swell of pride, even now. We cheered, grabbed each other’s arms and jumped up and down, our fists raised to salute the acoustic tiles overhead and, presumably, the stars beyond.

Then I wet my pants.

I’d been holding it for a while, my bladder bursting with the pop we’d been swilling all day long, dancing back and forth on my feet with anticipation and, to be honest, growing discomfort at the pressure in my lower abdomen . . . but unwilling to pull myself away even for a few minutes, lest I miss anything that happened.

“There are faint rustling noises from the darkness behind you.”

We’ve all been there, so many of us. We’ve explored the cave, solved it’s puzzles, sounded it’s depths. And yet, not one of us saw the same thing

This was the strength of those games, Adventure and the ones that came after. They were nothing more than text on the screen.

We made them up ourselves, as we were playing them. That was how you played them.

The intimacy of that kind of interaction with Art barely exists today in any other form.

Somewhere along the way, people started referring to comic books as “Graphic Novels”. As the readership grew up a little bit, it gained some maturity and respectability — which, in turn, it tried to impose on the medium.

The same is true of those text-based games. They’re called “Interactive Fiction” these days — a label that, to my ear, sounds a little too academic for something that was so engaging it not only caused a thirteen year old boy to wet his pants, but also compels a forty-two year old man to admit to it now. Proudly.

Books are words on a page, sure. We follow along and visualize our own version of things, as much as the author’s descriptions will allow us the freedom to do so. But even the movies can change those, though. Whether we like it or not. And long after the closing credits fade, we might find ourselves dodging box office artifacts during a rereading of a favorite book.

Not in these games, not in these games. They had just enough description to serve as a framework for the imagination, just enough for your mind to fill it.

They are some of the truest forms of Magic available in our reality.

We made our reality. I can describe the cave in detail to anyone who asks. It is staggering to me, even now, to realize that my cave would not resemble the one that Benny saw.

But we were both there, together. We saw it all.

“You’re at the end of a road. There’s a building in the distance.”

The table was octagonal.

Eight is a lucky number, for some. The eighth card of the Tarot is Strength or, historically, Fortitude. The woman and the lion. Kindness and perseverance, self-control. Discipline. It is associated with Hercules and Gilgamesh, among others. Heroes who performed tasks and fought monsters.

Eight sides makes a star with twelve points. Twelves facets to the Zodiac… Twelve faces in a deck of cards… Twelve people to decide the fate of the judged… There were twelve labors that Hercules undertook… And twelve men have ventured out into the dark to walk the surface of the moon…

Eight sides. A stop sign, perhaps. Like the one at the end of the road at which I was standing.

I sat at the table. Benny sat across from me.

I was at the end of the road. There was a building in the distance, a well house for a large spring.

I headed towards it to find out what was inside.

“Magic is said to work in the cave.”

Full disclosure dictates that I admit that this essay has been sitting inert on my hard drive for over a year now. From time to time, I’d open it up and tap a few keys . . . never really finding the thread of what I wanted to say, but wanting to say something about Benny and these games we used to play.

(I should say, he isn’t Benny anymore. Like me, he made use of his own magic to change his name and identity. Oddly enough, I don’t call him Benny but he doesn’t call me T.M. His magic was stronger, I suppose.)

We’re long out of touch now. We drifted in high school — to be honest, I was the one who drifted — and managed to reconnect briefly in college, long enough to be roommates. Annoying the hell out of him on a daily basis — and I was damn annoying to live with, as all of my college roommates can testify — was the final nail in the coffin.

From time to time, we’d bounce an e-mail back and forth. Maybe once every five years or so. Then Facebook showed up and gave us an excuse to, at least, nudge each other every year or so. One afternoon a few weeks back, he posted a photo on his wall: His son sitting in front of a chessboard, with a comment that Benny was teaching him to play.

I added my own comment, something along the lines of “After that, you’ll introduce him to Colossal Cave maybe?”

Later that night I was poking around YouTube, trying to shake off the general fog I’ve been under for the past few months. For some reason, desperate for distraction, I tapped in the words “Colossal Cave” and “Adventure” and discovered this little series in which D.G. Jerz introduces his son to the original Adventure game. Fun stuff.

Later that night I was poking around YouTube, trying to shake off the general fog I’ve been under for the past few months. For some reason, desperate for distraction, I tapped in the words “Colossal Cave” and “Adventure” and discovered this little series in which D.G. Jerz introduces his son to the original Adventure game. Fun stuff.

These led me, in turn, to Jason Scott’s excellent, magnificently dorky “Get Lamp” documentary — chronicling the history of the original Adventure and all the games that followed after.

It’s a great movie, if you’re as much of a dork as I am . . . so I highly recommend it.

Scott’s film brought it all back for me and, since nostalgia is powerful magic in and of itself, I went and dug out my old maps from my filing cabinet.

That I’d saved them all of these years says something, I’m sure. I knew I’d need them again, sooner or later.

Then I opened up this essay once more, threw away most of what I’d written, and put myself back in my seat at that odd octagonal table across from my friend Benny . . . back where it all started.

Back where I started.